HOME PAGE

WHY THIS

SITE?

A HISTORY

OF THE SCHOOL

THE

CENTENARY 1854-1954

THE

1930's

THE

EVACUATION TO RIPON

A LETTER FROM

MISS LONGWORTH

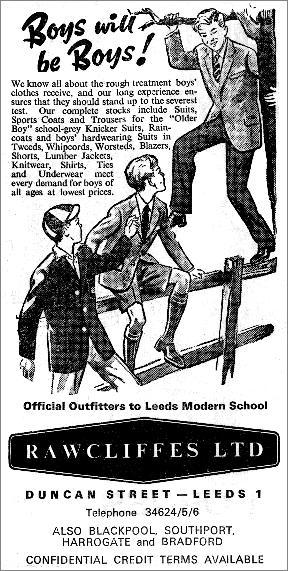

UNIFORMS

MORNING

ASSEMBLY

TEACHERS

LESSONS

WHATEVER

HAPPENED TO OLD SO-AND-SO?

MISS ARMES'

STORY

HYGIENE & SEX EDUCATION

SPORT &

SHOWERS

SPEECH

DAY

THE SCHOOL

SONG

SCHOOL

DINNERS

CRIME &

PUNISHMENT

A SCHOOL

REPORT

TO

JOAN

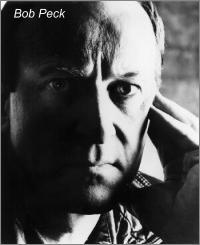

FAMOUS OLD

GIRLS

OLD

MODS

RETURN TO

SCHOOL

BACK TO THE

FUTURE

DOCUMENTS

PHOTOGRAPHS

THEN AND NOW

Well, there's no point in pretending they didn't exist!

There were very few ways you could see boys during the school day. You could -

We rarely saw them in the swimming pool. I think the schedules were arranged to prevent it. But occasionally -

"I remember the passageways under the school where we used to get changed for gym or playing hockey, and the terrific swimming pool, where we hoped to be able to flirt with the boys' class as they were just leaving." Maureen Whitehead '59-'64

"We never ever got a glimpse of the girls in the pool as when I was at the Mod our pool lessons were timed with military precision to avoid such glimpses. Occasionally however items of female attire were left behind which we dutifully handed in to the PE teacher after discussing the possible attributes of the wearer." Nigel Byrne '63-'67

The upstairs dining room was a good place, especially if you were a server. For a few fleeting seconds, you were face to face with a boy-server across the hatch. Nothing but a red-faced dinner-lady and a pile of steaming mashed potatoes between you! If you were lucky enough to be sitting at one of the tables nearest the hatch, you could possibly look at them whilst you were eating. However, in my recollection, this was rather like a Chinese meal - all anticipation and no fulfilment!

Were there any romances that first blossomed through the dining hatch?

"The only good thing about school dinners as far as I was concerned was looking through the gap for the boys - none in particular - all in general." Joyce Latto'59-'64

Going to the bottom of the field was definitely a better option. The middle of the field was, as we all knew, 'no man's (or girl's) land'. An invisible strip, equivalent to the width of the swimming pool block and as dangerous as a minefield, kept us apart. But the field was curved, not square. So, if one kept strictly to one's own side of the field, but went right down to the bottom, it was possible to meet boys. But prefects were always on the watch, so meetings rarely happened (except of course between the prefects!)

"I remember going down to the bottom of the playing fields to meet the boys. It wasn't fair - we got done by the prefects and they were doing exactly the same thing!" Jocelyn Laws '59-'65

"As a junior and senior prefect, I do not remember any fraternizing on the south end of the playing fields and was only aware of the demilitarized zone between the upper areas." Edric Clarke '31-'38

Eventually, it came to pass that boys and girls got together for ballroom dancing and for school plays. Very daring!

"When I was about fourteen (1968?) the call came in from the Boys School – their school production in the Theatre that year was Doctor Faustus, they were calling for girls to take parts in the Play – wow the excitement was intense! Eventually seven of the girls from my year group plus two Sixth Formers were lucky enough to pass the audition, so off we trouped to the Forbidden Building. We were beside ourselves as you can imagine.

"The seven younger girls were to play the Seven Deadly Sins – I was Envy ...very apt as I was so envious of the two Older Girls ... one played Helen of Troy and got to hold hands with the young man playing Faustus – what bliss. However, we had more fun in our dealings with the gorgeous young man who played Mephistopheles – he was Wicked!!

"I used to dream about him for years..."

"I also remember one [play] we did where Katy Brady did my hair up in something Greek and I felt transformed." Gill Crossley '59-'66

"As we progressed up the school we were allowed a link with the Modern boys in the form of after school ballroom dancing lessons, culminating in a tea dance type party when we could change into our own clothes." Sheila Galbraith '60-'67

"I also recall ballroom dancing lessons with the Modern School boys. A dating opportunity at last! I didn't have much luck." Katy Brady '59-'66

"I remember the ballroom dance lessons with The Mods..........slow, slow, quick, quick, slow! Rusty music coming from a record player with one of the teachers giving instructions but can't remember which one. I was lucky enough to have a handsome, blond 5th former called Paul and he apparently had quite a reputation at the Modern School. All happened when we were in the 5th form, after school hours in our hall or gym." Jackie Rowe '59-'64

1. Catch a glimpse of them leaving the swimming pool as we went in.

2. See them through the hatch in the upstairs dining room.

3. Meet them at the bottom of the field.

4. Hang onto the railings in the yard and peer through the space between the swimming pool and the dining room.

As The Mods have no Old Boys website of their own at present (aw, shame!), this page includes some basic info. about Leeds Modern School.

As The Mods have no Old Boys website of their own at present (aw, shame!), this page includes some basic info. about Leeds Modern School.

JOHN CRAVEN (Newsround)

JOHN CRAVEN (Newsround)